- Home

- Asli Erdogan

The Stone Building and Other Places Page 2

The Stone Building and Other Places Read online

Page 2

Exit through the double-paned door! Turn your back on the foreboding “T. Hospital, Pulmonary Patients Entrance” sign and walk quickly, looking straight ahead, until you reach the edge of the building’s giant shadow. Stand there at the border of the sun’s domain, take a deep breath, and then slowly, carefully, take the step that brings you out of the shadow. Suddenly, even the weak northern sun will be enough to warm your back, and you’ll believe it’s actually possible to erase your entire past and start anew! Let the sun play over your hair, let the forest cloak itself in vivid colors, let the shapes and outlines disappear, let truth become pure light.

Filiz thought of Nadyezdha, the sad Nadyezdha in Chekhov’s The Duel, who dreams of soaring to the sky by spreading her arms out in flight. Filiz often felt that she could have been a Chekhov character. Perhaps she could transform into a bird right then and there, but at most it would be a wooden bird. A bird whose wings weren’t made to fly but only to make mechanical noises, something lifeless and ridiculous. She was overcome with nervous excitement. Filiz wanted to cry and laugh, live and die at the same time.

“Come on Felicita! You’ve frozen up like a mummy! We’re going to be late.”

Joining in with Dijana’s cry was Gerda’s contralto, hoarse from tuberculosis and smoking: “You’ll miss the Amazon Express!”

They were a group of six women gathered at the door. “Three foreigners, three Germans, three tubercular, three asthmatic,” Filiz quickly classified them. “All of the Germans are tubercular, while we Third World-ers are asthmatic. Though one would have expected the reverse.” Martha and Gerda, the two tall blonde Germans, had managed to remain sturdy and strong, despite their tuberculosis. (In fact, Gerda wasn’t particularly tall or blonde, but in Filiz’s eyes, indifferent to personal details, the two were identical, and she had pegged them as the working-class women in their small circle.) Filiz was somewhat cowed by their physical strength, their boorish manners, but at the same time she secretly envied their stubborn determination to fend for themselves. The third German was Beatrice, a twenty-year-old with hollow cheeks, thin as a totem pole, an introverted heroin addict. With her short, chestnut-colored hair, her sad eyes that always seemed to be searching for something, and her adolescent’s stick-like body, the girl saddened Filiz. Dijana was the trickster, the red fox popping out from behind every rock. She didn’t give a damn or get rattled by anything. Except for being called Yugoslav instead of Croat. And then there was Graciela, the Argentinian…

The only patient in the sanatorium who was as isolated as Filiz — perhaps even more so — was Graciela. Unanimously described as “distinguished, elegant, cultured,” privileged from birth and quite well off, her presence among the pulmonary patients was an example of life’s cruel sense of humor. She was only a little over five feet tall (even shorter than Filiz), dainty and petite. Her straight hair and bangs, her “Marlene Dietrich eyebrows” — which she plucked religiously, even in the hospital — and her almond-shaped eyes, with a gaze as warm as it was icy, had earned her the moniker of “Evita.” She was the favorite of the doctors and nurses, who treated her as if she were a fragile antique vase. She somehow made everyone feel that she should be treated delicately. But Filiz had recognized the hardness in that perfectly composed face of a porcelain figurine. Graciela had a smile that frightened people. She reminded Filiz of her primary school teacher, dainty and chic in her scarves, and an expert tormentor in the classroom.

When she first saw Graciela, Filiz had thought she was a visitor who’d mistakenly walked into the patients’ cafeteria. Graciela was seated by the window, at a table with one chair. She was wearing a tight, black velvet skirt and a striking blouse unbuttoned to reveal her cleavage. Between her lovely breasts hung a gleaming, heart-shaped pendant. Sheer stockings and a pair of high-heeled, buckled “tango shoes” completed her look. Among the patients with unwashed hair, walking around in sweats and sandals, Graciela stood out like a rare tropical flower. And then one day Dijana, the hospital gossip, had burst into Filiz’s room and disclosed a secret:

“You know that Argentinian? Evita is just like you.”

“What do you mean ‘just like me’?”

“I mean a political refugee. Prison, torture, all the rest. That’s how her lungs gave out, in fact. Her ex-husband was a diplomat, both of them came from wealthy families with deep roots and influential friends. But, it turns out, the man stepped on somebody’s toes and a warrant was issued for his arrest. He fled in a matter of hours. Leaving his wife behind. For two months they tried to get Graciela to talk, but she wouldn’t reveal his whereabouts. And maybe she didn’t know. Can you believe it? That little kitten of a woman?! Don’t be fooled by appearances.”

This was a devastating blow for Filiz. It felt like a mockery of her deepest agonies, denigrating her personal history, her very being. She had crafted an image of herself as a mythic hero, and only by worshiping this hero could she go on with her life. Her dreadful past, the memory of it, was the necessary proof of her existence and it claimed a sacred corner of her soul. But now that conceited woman had defiled her icons. What right could she have to the same tragedies as the strong, brave, principled Filiz (that’s how she described herself), who had paid such a high price for her beliefs? And for what had Evita suffered? The love of a potbellied, contemptible man with two mistresses!

The procession of sick women walked along the narrow asphalt road that twisted and turned like a gray snake on its way to the T. Valley. At the very start of the journey the group had split in two, like a cell dividing. The leaders, Dijana and the two burly Germans, started up a trivial conversation. A rambling Saturday afternoon conversation on topics of absolutely no interest to Filiz. It began with the usual nitpicking complaints about the doctors — the female doctors were treated with jealousy while the handsome male doctors were flattered. Then they took up the subject of the cafeteria: the food and coffee were roundly condemned, as were the shows on TV. Next, they compared the charms of Banderas and Pitt, with the Germans rooting for Banderas while Dijana — a fan of the Anglo-Saxon race — championed Pitt. Finally, they dredged up a a few random memories from the time before they were hospitalized… In the factory where Martha had worked four years ago, a female worker was found completely naked with her throat slashed. Gerda also had a few murder stories in the deep-freeze of her memory, one of which she took out to reheat and serve. Dijana, whose family lived in Bosnia, didn’t say a word about violence; she hid behind a silence that loomed like an avalanche.

Beatrice, never quite sure of where she belonged, walked by herself, alone in her inner world. She was trying to drink in, sip by sip without wasting a single drop, the extraordinary September afternoon, the emerald-green valley spreading before her, and the two hours of freedom. She looked happy, and this happiness on her ruined young face was even more moving than a sorrowful expression.

Filiz ended up walking alongside Graciela, and she searched for something trivial to talk about.

“To be honest, it’s surprising to see you on the Amazon Express.”

“Why?” asked Graciela sharply. A cold flame shone in her eyes — a hint of the molten ore, the anger hidden for years at the core of her being. “They didn’t tell you where we’re going, did they?”

“No, they’re keeping it a big secret.”

“It is indeed a very big secret, the Amazon Express.” (A mocking, scheming tone of voice, with a smile like a scar.) “Even you will be surprised.”

“I’m guessing we’re going to the village?”

Graciela brought her finger with its long, cherry-red nail, to her lips. “Shhhh,” she said. Like the picture of the nurse on the “Silence Please!” sign back at the sanatorium.

Filiz had neither the stamina nor the desire to continue the conversation. She concentrated on enjoying the walk. She was going to be released in eight months; she was walking in fairytale woods, she was taking in the air, pure and delicious as water. Air that filled her tired lungs, cleansing them of the grim

e of the past. A tender, generous sun, an infinity of green stretching to the horizon, and the simple, unadulterated, glorious happiness of being able to walk to her heart’s content. Unconstrained. With no closed doors in sight… Ward doors with iron bars; sound-proof hospital doors with room numbers and lubricated hinges… A healthy person would never know the sublime pleasure of being able to use one’s legs to carry oneself forward freely. Filiz took note of the forest’s incomparable scent. It wasn’t as sweet and tame as the smell of the freshly mown hospital lawn; it was raw, primordial, dizzying. Perhaps it was the eerie silence that made her head spin. The T. Valley spread out before her like a densely woven green carpet; it was as though the hills, cascading one after another, were signaling to her. In the valley, where the autumn light had painted everything in sharp relief, sun and shadow were waging an endless turf war. The cross on the village church, gleaming like gold, was discernible from afar. “Everything is so light and carefree, it’s enough to make a person feel sentimental,” she thought.

Beatrice approached the two black-haired women, her palms full of wild berries. She must have resolved her identity crisis and decided that she belonged among the “foreigners.” The tragic bond attracting these two former prisoners was drawing Beatrice in as well, consuming her. Heroin had taught her loneliness, despair, devastation, and although she was the youngest among them, she was the one most intimate with death. She carried death in her childlike body. Others tried to believe in life, to commit to it, to belong, and they were still trying, but Beatrice had already renounced life by the time she was sixteen. Heroin, prostitution, hepatitis, tuberculosis… She’d suffered one fatal blow after another, but each time, at the count of nine before the referee could call the fight, she got back on her feet to withstand yet another beating.

“Would you like some wild berries?” (No, neither of them wanted any.)

“On TV last night, there was a program about Argentina. Did you see it?” (No, neither had.)

“They showed Buenos Aires. An extraordinary city. So moody! A bit like Berlin, the architecture, the cafés… They showed a neighborhood full of colorful houses, like the rainbow: Labakar…”

“La Boca,” Graciela corrected her. “Means ‘mouth.’ The birthplace of the tango.”

“That’s right. La Boca. The neighborhood of bohemians, painters, and musicians.”

“These days, it’s full of pickpockets and street peddlers.”

“Do you dance the tango?” Filiz asked excitedly.

“No, I’m not from Buenos Aires. I’m from Mendoza.”

(Somehow, I was sure this woman was from Buenos Aires and was a perfect tango dancer.)

“Mendoza?”

“On the border of Chile. A city at the base of Aconcagua.”

“Aconcagua. The highest mountain of South America!” (In Germany, even the junkies are well educated!)

Silence fell among them. The perfunctory conversation ended abruptly, as if cut off by a knife. As if the three women had absolutely nothing more to say to one another. Then, “Look. There. Look at that rope on the lower branch!” Beatrice couldn’t control the excitement in her voice. The two older women looked in puzzlement at this ordinary piece of rope. “A dwarf must have hanged himself here,” Beatrice continued, with the livid imagination of a twenty-year-old addict. But then she blushed, suddenly remembering that her walking companions were also quite petite. Thankfully, no one had taken offense.

When the procession of women left the road descending to the valley and turned west, toward the steep hills covered in dense woods, Filiz grew wary. So, they would not be visiting the T. village after all. Perhaps, like schoolchildren or prisoners on furlough, they had chosen an Edenic hideaway for their Saturday freedom. But if that were the case, there would be no need to rush or constantly check the time. The Amazon Express! Did it refer to the rainforests or to those women, the mythical huntress-warriors who severed men from their lives along with their right breasts?

They were no longer walking on a wide, sunny asphalt road, now they were advancing single-file on a difficult trail crowded by roots and underbrush. The true forest journey had begun. Even the filtered sunlight was green. Thorns greeted the forest travelers, irritating them at first, but then becoming increasingly aggressive. Heath, drifts of ferns, brown butterflies flitting among the branches, shy mushrooms hiding in secluded nooks and crannies, a journey filled with autumn flowers. Pearls of rain dripping from leaves, crystals of refreacted sunlight in the wet, sticky moss on trees… Seductive side trails guarding the hidden secret of their destination …

Filiz had always lived in big cities. She knew nothing about forests. True, she had been at the sanatorium at the center of the Black Forest for the past eight months, but there, too, the forest had remained inaccessible, abstract and mysterious. At night, the darkness that settled over the window like a black bird — the crowing that accompanied her nightmares — was like a hulking, deaf-mute guard who prevented her from returning to her real life — whatever “real” might mean. Now, having walked deeper into the heart of the forest, she was truly seeing it for the first time. This was much more than a simple introduction; it was the sudden encounter of two beings who had been completely unaware of each other’s existence. Which is why Filiz was shaken. She was suddenly face to face with a pure, primitive, magnificent, oceanic spirit. It had propelled her from her dusty, sterile, nutshell of a world and bade her listen to the chords of an altogether different existence. The forest had a wild, vibrant, pulsing rhythm. It was cloaked in strange shadows, contradictions, tremors; its secrets concealed by a quivering, gauzy mist. Trees, trees, trees… Ancient, solemn, imposing… Imperturbable, as if they had seen all the miracles and crimes on earth. Older than time itself… They had sunk their roots deep; for them, freedom did not mean propagating far and wide, but growing ever taller on their single-minded journey to the sky.

When they slowed down at the base of a steep slope, Dijana pulled Filiz aside.

“This isn’t the time, I know,” she tried to catch her breath, pausing a second or two. “But we need to talk tonight. I wrote Hans a letter.”

“The last one I wrote… that we wrote together, did you send it?”

Once she spoke aloud, Filiz realized how thirsty and out of breath she was. Her mouth was so dry that she had to work to peel her tongue off her palate.

“Of course, that same day. No reply yet. But wait — it’s been nine days already. Maybe it got delayed at the post office. Plus, Hans tends to be a bit slow.”

“You believe he’ll reply though, right?”

Something like lightning flashed in Dijana’s amber-colored eyes, and her face clouded over. “I don’t believe. I feel it.”

About two months earlier, on her way back from a visit to the chief physician’s office, Filiz had seen Dijana in one of the telephone booths on the ground floor. Gripping the phone with both hands, she had been talking and crying at the same time. At first, she thought Dijana had received another piece of terrible news from Yugoslavia — it was in one of those booths that a gravelly voice on the other end of a bad connection had told Dijana that her sister had died in Bosnia. But this time the news was different. Dijana’s last lover, the tall, clever Hans, had grown exceedingly weary of this tubercular, ruined woman with her wheezy breathing and the bags under her eyes, the depressing hospital visits. Together, Filiz and Dijana had written five letters to Hans, but even Filiz’s sensitive and persuasive pen had not succeeded in getting him to write back.

“If I were you, I’d erase him from my mind.”

Filiz knew she was being heartless and aggressive, but she was very tired. She was drenched in sweat and terribly thirsty. She could feel the veins pulsing in her exhausted legs. She had no energy to deal with Dijana’s troubles.

“You have a heart of stone!”

“There may well be some stones in my heart. But alright, how about we try to make him jealous?”

“In the middle of the woods?

If only these trees rained men instead of pine cones!”

“We could insinuate that there’s a budding romance between you and one of the doctors. We’ll choose someone with features completely the opposite of Hans’. ‘A young surgeon,’ ‘his long slender fingers,’ ‘walks in the forest under the moonlight,’ and so on.”

Dijana smiled, quickly recovering her lightheartedness. She certainly had an exceptional smile; it completely transformed her incongruous features. It was unguarded, sincere, and subtle enough to make an immediate and deep impression. Filiz thought she had never seen an expression that articulated happiness so simply.

“I want him back.” Dijana’s mood seemed to darken again.

Her voice trembled with an indistinct, imploring tone. If she could just prove that she truly desired Hans, she seemed to think, perhaps some divine justice would summon him back to her. The dark shadow hiding behind her happy-go-lucky demeanor revealed itself only in moments like this. Dijana kept her true self secret, hidden in deep underground tunnels like some monster who mustn’t see daylight.

“He’ll come back, I’m sure,” Filiz forced a reassuring tone, stifling her feelings. She enjoyed neither lying nor talking about men. She didn’t believe in love; she couldn’t remember if she ever had, even before she spent thirty-three days in a cell filled with blood and screams.

“Dijana! Dijana!”

“Yes, what is it?”

“We’re late! We’ll never get there at this rate. We need a short-cut.”

“Wait, let me catch up. We’ll take a look.” She ran toward the Germans, her strides shaky.

Filiz sensed Graciela’s burning eyes on her back and turned to face her. Their two gazes met — profound, intense, wounded — and a rapport beyond words was instantly established between them.

“If you want to be happy, happy, trust the little girl, the strength of her faith.”

Graciela’s face remained perfectly still. Had she understood? Without a doubt.

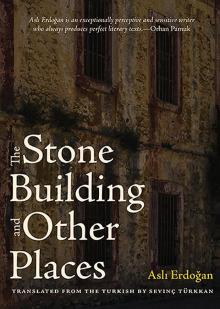

The Stone Building and Other Places

The Stone Building and Other Places